Why did WW1 soldiers wear drag?

Theater troupes needed "female impersonators" but their performances were sexually charged

(Library and Archives Canada/PA-1950)

Photos of soldiers in drag during the First and Second World Wars get posted online a lot, because it’s funny to see men wearing dresses next to enormous industrial weaponry. One specific set of photos gets posted repeatedly to Reddit, depicting WW2 British naval gunners manning their artillery piece during the middle of a drag show: there’s this post, and this one, and this one with a clickbait-y caption. Because drag shows are part of the culture war at the moment, these photos inevitably stir up debate about whether we should treat crossdressing in wartime as queer behavior or just a case of guys bein’ dudes - that is, whether these performances were meant to be arousing or just silly. Culture war aside, it’s an interesting question that gets into the topic of how war changes gender roles, especially for men. I’ll focus on the First World War because I know more about it, but everything here applies to drag in the Second World War as well.

Drag shows were a common form of entertainment for soldiers during the First World War, but they remain a complex topic for historians to explain. Soldiers wrote about them in contradictory ways. Often they presented drag as a joke or a necessity for putting on plays with female roles. Usually, I think we should take historical actors at their word without trying to read for hidden beliefs or desires, but cross-dressing is a sufficiently complicated behavior that it does require historians to examine the psychology behind it a bit more. During the war, strict Edwardian gender roles came into conflict with the unprecedented sexual freedoms afforded to men deployed abroad. Drag shows were undoubtedly meant to be humorous. However, they also became spaces where men experimented with homoerotic behaviors introduced to them by the war.

That said, there were obviously few women present on the front-lines, so men did need to act their parts in shows, and did so quite well according to our sources, like this British soldier who fought in Macedonia:

"They were simply known to us as F.I.s, that is female impersonators as I doubt whether the name 'drag' had been invented then. Those who took male parts and all our regulars had their special 'pets' and jealousy amongst the 'ladies' was, in consequence, rampant, one particular chorus girl, for instance, was much discussed, praised by some and blamed by others, because during the singing of a special hit by one of the principals, she would persist in making goo-goo eyes and at the audience and drawing all the attention on herself."

Performances like this were not unique or secretive but a sanctioned and common form of entertainment on all fronts throughout the war. At least 80% of British divisions had a "concert party," as these theater troupes were known, made up of enlisted men and junior officers. Official training manuals recommended them alongside other activities like sport as key to maintaining morale and building esprit de corps. And these performances almost always had men performing in drag.

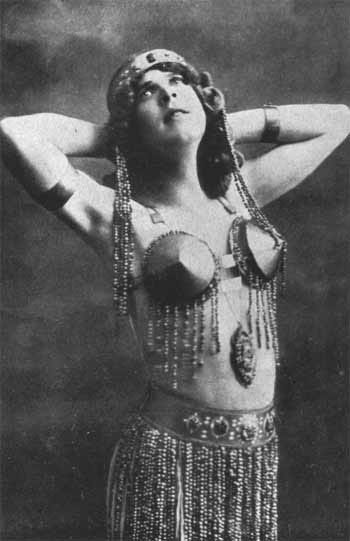

(Cross-dressing was not limited to the British. Emmerich Laschitz was “Siberia's most famous female impersonator,” among German and Austrian prisoners of war in Russia. His most popular role was Salome, in a 1917 production of Oscar Wilde’s play for the Achinsk prison camp. Soldiers and POWs enjoyed considerable artistic freedom compared to the home-front - the play was so controversial that it was not performed in Britain until 1931.)

In letters and diaries, soldiers went out of their way to de-emphasize the transgressive and homosexual nature of these drag shows, even the relatively few sources which criticized these performances. Soldiers explained their attraction to men dressed as women by stressing how realistic and feminine the performers looked. "It was quite impossible," wrote another soldier fighting the Bulgarians in Macedonia, "to realise that these delicate young creatures were young men who drove heavy motor lorries or threw bombs at the Bulgar. It all seems to show that the English beauty is essentially masculine. Take a likely looking young man and dress him up suitable and he makes quite a pretty women." The implication in letters such as these is that if the performer in drag made a convincing enough woman, than there was nothing queer about being attracted to him.

Yet wartime caused a lot of sexual confusion. It disrupted "regular" sexual relations in Europe, removing men from home and women and putting them in a social world which revolved around their male comrades. Soldiers in dangerous conditions necessarily developed strong bonds, relying on each other with their lives, living in close proximity to one another, taking care of each other. These relationships could become very tender, with men taking on roles performed by wives or mothers at home. A junior officer’s tasks were often equated with mothering: making sure men had enough to eat, making sure their clothes were in good condition, checking their feet for blisters and sores. Soldiers took care of their officers in return. Each British officer was assigned a personal servant who did his cooking and cleaning, and the ties between officer and assistant could become emotional - in The Lord of the Rings J.R.R. Tolkien deliberately invoked the love between officers and servants to explain Frodo and Sam’s relationship. Of course, in the largely anonymous, all-male environment of barracks halls, trench lines, and prison camps, there were plenty of opportunities for men to experiment for the first time with actual queer love. But even straight men found themselves in intensely strong male relationships which they would not have experienced in civilian life.

Drag performances in part functioned as public catharsis for the uncharted sexual territory of the war; they made it OK to feel love and attraction to another man by having him dress as a woman. It helped men to rationalize that they were fully heterosexual after all. But conversely it also allowed men to escape the rules of accepted heterosexual behavior, giving them a space where male-male intimacy was not only tolerated, but accepted through the presence of officers, and celebrated by being fun. Drag performances were a place where soldiers could safely cross the lines of gender behavior, lines that the war had already blurred.

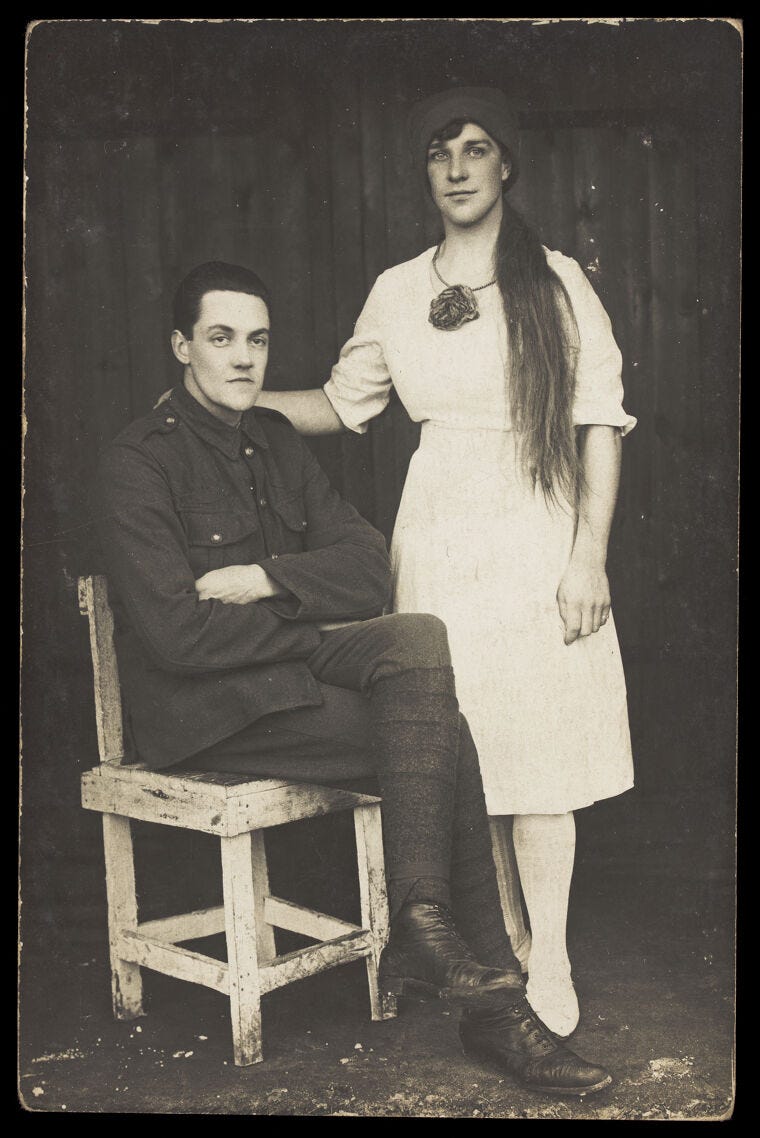

(Two prisoners of war, one in drag; Digital Transgender Archive.)

Attraction to drag performers went far beyond appreciation for their skill at dressing up. The best stars commanded real adoration. Ross Hamilton, who played “Marjorie” for the Canadian vaudeville troupe the Dumbbells, had to change back into uniform immediately after performances or else “he would actually get mobbed on his way back to the barracks." After one play a senior officer snuck backstage with flowers to ask Marjorie on a date, forcing Hamilton to escape through a bathroom window. Admirers wrote poems and love letters to female impersonators, like one German general who told his favorite actress “you are like a flower, so delicate and pretty and pure.” The performer Emmerich Laschitz explained how in Russian prison camps, “each female impersonator had a circle of fans and admirers, whose assignment was to wash and iron undergarments and articles of women’s clothing. All the work was left to the chambermaid, even if that was a gray-bearded reserve officer.” These are clearly cases of men being attracted to other men in drag. There's a scene from Jean Renoir's masterpiece Le Grande Illusion which does a great job conveying the sexuality of these performances, which could be very homoerotic.

(Ross Hamilton as Marjorie; Nova Scotia Archives, MG 1 2785)

But homosexual behavior and drag performances were only tolerated in the topsy-turvy, all-male world of the front. Elsewhere, society deemed drag worryingly transgressive of proper gender norms. Take the example of Victor Wilson, who attempted to proposition some fellow British soldiers in Dundalk in June 1918 while wearing women’s clothes. Beyond the homefront or approached singly the men may have said yes, but the three men together notified the authorities and helped arrest Wilson. Tabloids ran the story as a shock piece: "IN FEMALE ATTIRE / MASQUERADED AS GIRL TO HAVE FUN WITH SOLDIERS." But in the trenches or in prison camps far behind the lines, where the gender spheres of Edwardian life had temporarily broken down, such behavior would probably have been accepted.

Sources:

Alon Rachamimov, "The Disruptive Comforts of Drag: (Trans)Gender Performances among Prisoners of War in Russia, 1914–1920. The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, no. 2 (2006): 362-382.

David A. Boxwell, "The Follies of War: Cross-Dressing and Popular Theatre on the British Front Lines, 1914-18," Modernism/modernity 9, no. 1 (2002): 1-20.

Jason Crouthamel. An Intimate History of the Front: Masculinity, Sexuality, and German Soldiers in the First World War. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014.

Justin Fantauzzo and Robert Nelson. “A Most Unmanly War: British Military Masculinity in Macedonia, Mesopotamia, and Palestine, 1914-1918.” Gender & History 28, no. 3 (2016): 587-603.

(This article is a good discussion of cross-dressing on theaters besides the Western Front, but I don't agree with the argument. The authors buy into the cognitive dissonance that soldiers expressed and don't see drag performances as homoerotic, whereas I do.)

Sarah Worthman, “2SLGBTQ+ Persecution in the First World War: An Untold History of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.” The LGBT Purge Fund, March 17 2023.