What were relations between French-Canadians and the French like in WW1?

And what did Francophone and Anglophone Canadians think of one another?

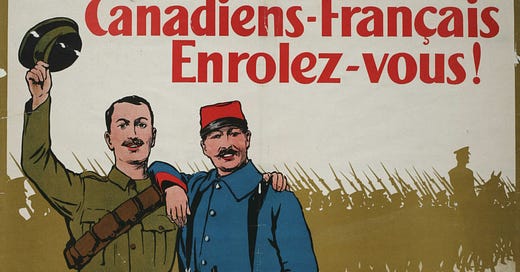

(An enlistment poster asks French-Canadians to fight alongside their French cousins, a recruiting tactic that didn’t seem to have much success; Canadian War Museum)

This was one of those questions that I genuinely didn’t know the answer to before I responded, but it interested me enough to research a response, which led me down the rabbit hole of Francophone-Anglophone relations in Canada, always a touchy subject, particularly during the war years. Ironically the answer doesn’t have much to do with the French themselves, who in general seem to be barely aware that there is a French-speaking Canadian population. French-Canadians don’t think about the French a lot either, but they do think a lot about their place within the Canadian nation, which is what I wrote about here.

Q: What was the relation between French-Canadian troops and the French population and army in World War 1 and 2? How did they view each other?

A: Most histories of French Canadians in the war focus on their non-participation, rather than their activities at the front. Canada did not introduce conscription until 1917, which led to a bitterly-divided vote in the December elections of that year. From the beginning of the conflict Anglophone Canadians had accused French Canadians of shirking their duties, and it was true that few French Canadians volunteered to serve. Only 1000 Francophone men went abroad with the first Canadian Expeditionary Force contingent in 1914, although it should be pointed out that native-born Anglophone Canadians also volunteered in small numbers. The CEF was disproportionately British-born, with immigrants from Britain, 10% of the Canadian population, making up almost half of Canada's overseas military strength throughout the war. As for French-Canadians, they did not have strong traditions of service in the Canadian military, had not experienced the militaristic culture of pre-war Anglophone Canada, and did not identify with the British Empire or its defense. Moreover, a wartime economic boom for Canada's industrial and agricultural sectors took off in 1916, which meant most men preferred to stay home and work.

According to the historian Serge Durflinger, only 15,000 French Canadians volunteered during the war. For one thing, the 13 battalions raised in French Canada during the war tended to target urban Anglophone recruits instead of men from the French-speaking countryside. Only one French-speaking battalion, the 22nd or "Van Doos," went overseas in 1915. Other French units mostly sat around in garrison duty or were broken up as replacements for the Van Doos, like the 163rd Battalion, which spent the war in Bermuda before its troops were parceled out as reinforcements to the front.

The government and supporters of the war effort tried to rally volunteers by appealing to Francophone solidarity, as with the recruitment poster in the image posted above, but it doesn't seem to have had much effect. Canadians felt distant both historically and morally from the scandal-ridden, anti-clerical French Third Republic. The anti-conscription politician Henry Bourassa criticized the French government in 1918 for "trying to have us offer the kinds of sacrifices for France which France never thought of troubling itself with to defend French Canada." Of course, Bourassa spent a lot more time criticizing his own government, whom he called the "Prussians of Ontario" and whom he claimed were trying to wipe out the French population by herding them off to die at the front. In general, the French Canadian war experience was defined by opposition to Anglophone Canada rather than support for France.

The relatively small amount of French Canadians who made it to the Western Front also seem to have been more preoccupied with their fellow Canadians thought of them. Before participating in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the 22nd's commander Lt. Colonel Thomas-Louis Tremblay wrote in his diary that “this is our first significant attack; it must be a great success for the honour of all French Canadians we represent in France." Tremblay's hope was that French Canadian success would prove that the "Canayens" were not "slackers," as so many Anglophones accused them of being. Major Georges Vaniers similarly felt that the battalion was fighting "for the honour of all French Canadians."

On the other hand, French and French Canadians saw each other the same way British and Americans did: as very distant cousins. Few French living near the front appear to have known that there were French-speakers in Canada, as Vaniers wrote home to his mother. “The people hardly understand how we happen to speak French and wear khaki. Very many of the French inhabitants were ignorant of our political existence as a race apart in Canada." For their part, French Canadians with their rural accents reminded the French of peasants "from Picardy and Normandy."

As the war went on some of the Van Doos seem to have grown fond of France, although they never quite identified with it. Vaniers' letters talk of admiration for the "greatness of Joffre and the French Army," their "dash and determination," and made him feel that "if we had more like them in Canada, we would be a noble, a better race." In comparison to their generally positive feelings about France, few French Canadian troop seem to have written about their feelings towards Britain, either positively or negatively. And although they liked the French, French Canadians like Vaniers and Tremblay spoke far more in their letters about missing "our dear Canada."

As a final note, Anglophone Canadians did indeed identify French Canadians with France, far more closely than the French Canadians themselves. When the Van Doos sailed off for England from Nova Scotia, the local brass band played la Marseillaise. In return the Van Doos struck up "God Save the King." Just as Anglophone Canadians viewed their French-speaking neighbors as "French," French Canadians saw them as "British." Yet for almost all native-born Canadian soldiers during the war, only Canada was truly home. Captain Georges Francouer spoke for many Canadians, Anglophone and Francophone, when he talked about how he had spent Christmas Day 1915. "We thought of our beautiful Canada, and we wonder what the New Year has in store for us—a speedy return to our country, or a wooden cross."

Sources:

Robert Brown and Donald Loveridge, "Unrequited Faith: Recruiting the CEF 1914-1918," Canadian Military History 24, no. 1 (2015).

Raphaël Dallaire Ferland, "Patriotism and Allegiances of the 22nd (French Canadian Battalion), 1914-1918," Canadian Military Journal 13, no. 1 (2012).

Mélanie Morin-Pelletier, "French Canada and the War," 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, 2016.